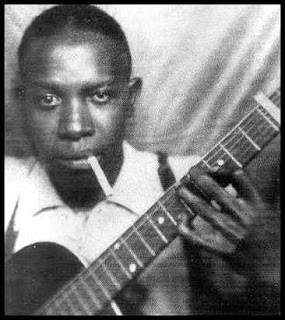

All we know about him are 29 songs, two photographs and little pieces of his biography that ends into a violent death at the age of 27. With this short of material is almost impossible to create a myth, but HE IS A MYTH. After 65 years of his disappearance, his 29 songs have become uncountable times versionated classics, experts continue seeking information about him and the number of books, volumes and articles talking of his peculiar life and work is huge. That’s why this extraordinaire blues singer is the choice to go deeply into in my essay. Because of that and because of the grace he was blessed to express his feelings.

He was just a rambling musician. He was rambling so fast, in fact, that he rarely gave anyone more than a glimpse at his shinning star. Indeed, he hardly received more than a casual, passing glance, and was seen at the time by only a few of his musical associates and even fewer fans to be consummate artist he was.

He had a very unfortunate life.

Robert Johnson was born May 8, 1911, in Hazlehurst, Mississippi, to Julia Dodds and Noah Johnson, the man whom she favored in Mr. Dodds’ absence. After very hard and unsettling seasons in migrant labor camps with his mother, they settled in Robinsonville, 20 miles south of Memphis; after having several stepfathers because his father abandoned them when he was a child (Robert didn’t ever know him); after this hard childhood, Robert took an interest in music in his early teens. His initial attraction to the jew’s harp was soon supplanted by the harmonica, which became his main instrument for the next few years. He and his pal, R.L. Windum, traded verses of songs and accompanied each other on harps until they were both young men.

The guitar became an interest during the late 1920s. He made a rack for his harp out of baling wire and string and was soon picking out appropriate accompaniments for his harp and voice.

His beginnings in the world of Blues, first with the harmonica and shortly after with the guitar took place near Robinsonville, where he lived, an important place for the main performers in those times. Musical godfathers as Son House and Charlie Patton helped him and he got the inspiration he could handle. Step by step, he made up his vocational training beside of the best musicians until become one of them.

Robert’s private life got serious about this time as well. A good looking boy, he had very little trouble making himself popular with the girls. In fact, he had more trouble keeping his hands off them, his arms from around them, and himself away from them. Eventually, it would be his downfall, but for the time being, most of the ladies were single. One particular one caught his eye, and he asked her to be his wife.

Even though Robert was playing music a great deal at this time –mainly the popular recorded blues of the day- and learning even more from Brown, Patton, Myles Robson, Ernest “Whiskey Red” Brown, and other locals, he was reluctant to consider himself anything but a farmer when he married Virginia Travis in Penton, Mississippi, in February, 1929. Virgina became pregnant that summer, and Robert was not only a proud expectant father, but, naturally, a protective one as well.

Robert’s pride was short-lived, however. Whatever hopes and dreams he may have had for his wife and family-to-be were all dashed in one fell swoop. Both Virginia and the baby died in childbirth in April 1930. She was 16 years old.

If anything soothed Robert’s wounds, it may have been his music.

The jook joints of the road gangs and lumber camps set the stage for Robert, and bluesman Ike Zinnerman became his coach and mentor. By then, Robert had found out that women would provide everything else for him and in Martinsville, a lumber camp a few miles south of Hazlehurst, he singled out a kind and loving woman more than ten years his senior, who had been married twice before and had three small children. Robert and Calletta “Callie” Craft were married at the Copiah County courthouse in May 1931 and kept their marriage a secret from everyone. She idolized him, she treated him like a king.

Callie loved to dance and she freuently webt with him in his playing jobs. He liked to tap dance and his agility is still recalled with a certain respect.

But respect wasn’t something Robert received in abundance. He wasn’t a rough-and-tumble guy. Robert Johnson was a small man, small boned. He had long delicate fingers, beautiful hands, enviably wavy hair, and appeared a good deal younger than he acted. Phisically, he wasn’t the type of man who commanded much respect.

Ike Zinnerman was born in Grady, Alabama, in the early years of the century and had always told his wife that he had learned to play guitar in a graveyard at midnight while sitting on tombstones. Robert used to spend all night at Zimmerman’s to learn what he could about music. He’d play the same tune over and over until he got it just like he wanted it and thought it should be. He began keeping a little book to write his songs in and he’d go off into the nearby woods and sing and pick the blues to himself.

On Saturdays, he’d practice his lessons by performing for the public on the steps of the courthouse during the day and at any number of local jook joints from Saturday evening about dark, sometimes until late Sunday night. At first he and Ike played together, but as time went by, he became more confident of his own abilities and played more by himself.

Occasionally he’d hitchhike out east to Georgetown or up to Jackson to play with Johnny Temple and his friends, but he usually stayed around home. In later years, he was content to be at home wherever he was, but at that time, home was where his wife was.

The early 1930s was a very important stage in Robert Johnson’s life. During his stay in Copiah County, he developed the personal traits that marked him as the man he was to be the rest of his life. Most important though, his musical talent flowered and bloomed in Hazlehurst, and when he thought he was ready for more exciting territory, he packed up Callie and the kids and slipped away to the Delta.

Robert deserted Callie and she died a few years later. Although Robert returned to Copiah County in later years, neither she nor her family ever saw him again.

A trip home was in order. He’d retruned to Robinsonville to see his mother and kin as well as to show himself off to Willie and Son, and he stayed around for a couple of months playing on the street corners and in the jook joints. He would continue to return and stay a few months at a time, but it would never be his home again. Robinsonville was a farming community, and he was finally no farmer.

One of the most wide-open, musically active towns in the Delta in those days was on the Arkansas riverside, and it became Robert’s home base for the rest of his short life. He tokk the little town of Helena, Arkansas, to be his own.

All the great musicians of the era came through Helena. “Sonny Boy Williamson”, “Robert Nighthawk”, Elmore James, “Honey boy” Edwards, “Howlin’ Wolf”, Calvin Frazier, Johnny Shines, and countless others performed in Helena’s and West Helena’s many night clubs and hot spots. Robert had his chance to meet and play with them all –and he did- and left his mark on most of them, too.

Robert Johnson was protective about his style of playing music and was acutely aware of overly watchful eyes. He wouldn’t show aspiring musicians how to play his songs, that was his business and his living. If he asked how to play something, he might say, “Just like you”, and be through with it. If someone was eyeing him too closely for his comfort, he might get up in the middle of a song, make some feeble excuse to leave the room, and be gone for months.

There was one special young fellow to whom Robert took a liking, undoubtedly as a result of his living with the boy’s mother. Estella Coleman was good to Robert. She loved him and cared for him. Robert wanted to repaid her kindness and became a mentor to her son. He was named Robert, too, and wasn’t much younger than him. Although named Robert Lockwood Jr. after his real father, he was soon known as “Robert Jr.” after his “stepdaddy”, Robert Johnson.

The practice of protection and disappearance all seemed very weird until research undertaken in the early 1990s has revealed that Johnson may have been guarding a method of tuning his guitar that he wanted no others to discover, not even his own student.

In any event, and for whatever reason, Robert Johnson became a stone traveler. He developed a penchant for it. Awake or asleep, anytime of the day or night, he was ready to go anywhere, even back the way he’d just come. Travelling was, in and of itself, the main thing, like a way of feeding himself.

Moving around the way he did and playing into many different places to so many different people all the time, he had to, out of necessity, be able to play almost anything which was requested of him. In addition to the blues for which he was known, he developed a very well-rounded repertoire that included all the pop tunes of the day and yesterday, hillbilly tunes, polkas, square dances, sentimental songs, and ballads. Among the more common pieces he played were, “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby”, “My Blue Heaven” and “Tumbling Tumbleweeds”.

In having to learn the many kinds of music which he had to play, Robert developed a very unusual talent. He could hear a piece just once over the radio or phonograph or from someone in person and be able to play it. He could be deep in conversation with a group of people and hear something –never stop talking- and later be able to play it and sing it perfectly.

Robert came in contact with a great many people in his travels and they helped to spread his fame. Naturally, at least half of them were women, and most of them were crazy about him. The other half, the men, would go crazy if their women liked him too much. Robert was pretty hard on “working girls” –they were too tough for him, too- but if he was going to be in any one place for a while, he developed a technique of female selection that generally kept him out of trouble and well fed and cared for, to boot.

As soon as he hit town, he’d find the homeliest woman he could. A few kind words and he knew he’d have a place to stay anytime. His reasons were threefold; a.- she probably wouldn’t have a man. b.- no one was likely to be after her or upset if he was with her. c.- just a little attention would bring him nearly anything he wanted. Accordingly, Robert could be the nicest guy in the world to the ugliest witch in town.

He had developed a taste for booze, gambling, and an occasional smoke, too, and although he never became habitual with any of them, he did drink to excess more than a few times. Sober, Robert Johnson frequently became a pensive man. Often he could be found sitting alone in a deep study. Over the years, his behaviour became progressively moody and erratic, but a drink or two, especially if he had purchased them for himself and a few friends, transformed him into the life of the party.

By the middle 1930s Robert Johnson had been a professional musician for quite a few years. He was very well known all through the Delta areas and had followings in southern Mississippi and eastern Tennesse, too. He had wanted to make records for some years, as his mentors Willie Brown, Son House, and Cahrlie Patton had done. He wanted to join the ranks of the musicians to whom he had listenes and from whom he learned off phonograph records, Kokomo Arnold, Leroy Carr, Skip James, Lonnie Johnson and others. And so he made contact with the one fellow in Mississippi that he knew would know how he should go about it.

H.C. Speir ran a music store in Jackson, Mississippi, and had an informal studio for making records for personal use on the premises. He was also employed from time to time as a talent scout by various record companies. Paramount recorded a great many people upon his rsommendation and he was known in the industry as the possesssor of an acute ability to be able to determine on what black people would spend their money. During the time when hardly anybody knew what anyone would buy, this was a great and useful talent, and Speir was constantly in demand for his advece and serveces.

By the time Robert was ready to record, Speir had just concluded a deal with the American Record Company that left him rather embittered. Speir was so discouraged about a trouble with this company and when Robert contacted him, all he was willing to do was take is name and pass it along to someone who might do him some good.

Ernie Oertle was the ARC salesman and informal talent scout for the mid-South in the late 1930s, and surprisingly, it was to him tha Speir gave Johnson’s name and address. After an audition, Oertle decided to take Johnson to San Antonio to record.

Robert’s first session in November 1936 yielded the song for which he’s most widely remembered, “Terraplane Blues”. It was his best seller and a fair-sized hit for Vocalion Records. Although six of Johnson’s eleven records were still in the Vocalion catalog by December 1938, he wasn’t recalled that spring nor even the following summer. Vocalion did release one final 78 in February 1939, but that was probably due to a great deal of interest in hin by John Hammond.

Robert left Helena with Johnny Shines and Calvin Frazier, who really had to leave –he had killed a couple of men in Arkensas- and they struck out on a trip that lasted about four months. They took Highway 51 north to Chicago through St. Louis, where they met many of the city’s famous bluesmen –Pettie Wheatstraw, Henry Townsend, Roosevelt Sykes, and others-. In Detroit, their next stop, they hooked up with a broadcasting preacher and appeared with him on radio as well as in his personal appearances, both there and in Windsor, Ontario, Canada. Calvin stayed in Detroit and Johnson visited the East coast briefly, playing in New York and New Jersey.

During this excursion with Shines, Robert displayed a certain uneasiness with his traveling companion. Frequently he would slip away from him, and Shines would have to guess which way he went and try to catch up with him. It was an uncomfortable feeling for Shines, but he knew of no one better to follow and learn from, so he stuck with it to Memphis.

Robert’s musical approach was altered a bit; he began playing with a small combo. He used a pianist and a drummer in a Belzoni jook joint –the drummer had “Robert Johnson” painted in black letters across his bass drum- before a large crowd of people, a good many of them musicians. And he was able to play anything people wanted, he began to concentrate less and less on the blues. He may have gotten away from it almost entirely had it not been for some divine intervention.

It seems so ironic that for all of Johnson’s efforts to make himself known to the world through his music, better himself, and upgrade the status quo, at least for himself, he should be heard so distinctly by tho one person that had his ear open, pocketbook ready and the power and ability at his beck and call to assist him. And it’s even more ironic –indeed, tragic- that it was never to be.

Sometime in June or July of 1938, Robert left Helena and swung through Robinsonville to see his people before taking up a playing offer he had further down in the Delta. There was a jook joint out from Greenwood at the intersection of Highways 82 and 49E, a little place the locals referred to as “Three Forks”, “Three Corners” or “Three Points”. It was here that Robert played his last job.

It was a dangerous occupation being a musician in those days: musicians hated you if you played better than them. Women hated you if you cast your eye on anyone else. And the men hated you if the women loved you. A great musician had to be careful, especially if he didin’t care to whose woman was talking. And, by then, Robert was notorious for that.

Robert Johnson had been in the Greenwood locale for at least a couple of weeks, sharing Saturday night plays with “Honeyboy” Edwards, who lived in Greenwood. Robert had made friends with a local woman, who happened to be the wife of the man who ran the jookhouse at “Three Forks”. She would come into Greenwood on Mondays, ostensibly to see her sister, but, in fact, to spen tiem with him.

On one Saturday night of in July, 1938, there was the added attraction of “Sonny Boy Williamson”. He wore a belt of harps around hes waist in those days, and he was a familiar and popular rambling songster. “Honeyboy” wasn’t to arrive until after 10.30 p.m. By that time, Robert and Sonny were through for the evening. Sonny Boy had left, and never again would Robert perform his great blues.

Misician Houston Stackhouse was not there, but having been close to Robert at one time, he was curious about Robert’s death. He was also close to Sonny Boy and so, over a period of time, he was able to obtain a more complete picture of the events of that fateful evening. The tale Stackhouse received from Sonny was verified to the best of knowledge by “Honeyboy”, and so it is that we know how Robert Johnson met his fate.

From all reports, Robert began displaying his attraction to the lady he had been seeing during his time in the locale. He amy not have known, nor probably would it have mattered to him, that she was the houseman’s wife.

Sonny Boy had been keepinfg an eye on the evenong’s proceedings. He had noticed both the attraction Robert displayed for the lady, as well as the marked tension on the countenances of gertain persons in the house. He knew that it was a potentially explosive situation. He was ready.

And so, during a break in the music, Robert and Sonny Boy were staniding together when someone brought Robert an open half-pint of whiskey. As Robert was about to drink from it, Sonny Boy knocked it out of his hand and it broke against the ground. Sonny admonished him, “Man, don’t never take a drink from a open bottle. You don’t know what could be in it”. Robert retorted, “Man, don’t never knock a bottle of whiskey outta my hand”. And so it was. When a second open bottle was brought to Johnson. Sonny could only stand by, watch, and hope.

It wasn’t too long after Robert returned to his guitar that he soon could no longer sing. Sonny took up the slack for him with his voice and harmonica, but after a bit, Robert stopped short in the middle of a number and got up and went outside. He was sick and before the night was over, he was displaing definite signs of poisoning; he was out of his mind. It seems the housman’s jealousy finally got the best of him and someone laced Robert’s whiskey with strychnine.

He was young enough to withsatnd the poisoning, though, and he made it through the next couple of weekd. Eventually, he was removed from his room in the “Baptist Town” section of Greenwood to a private home on the “Star of theWest” plantation, where he received attention,... but it was already too late. He lay deathly ill and in his weakened condition, he apparently contracted pneumonia (for which there was no cure prior to 1946), and succumbed on Tuesday, August 16, 1938.

In late 1938, John Hammond began recruiting talent for his first From Spirituals to Swing Concert. He called Don Law in Dallas and asked him if he could round up Robert Johnson and get him to New York for his presentation at Carnegie Hall. Hammond thought Johnson the greatest of all the country blus guys and wanted him to fill one of the openinf slots in his show. Law could hardly believe his ears. He told Hammond he was making a big mistake, Johnson was so shy that he woukl freeze up in front of an audience. But Hammond replied that if Law wold just get in touch with him, he would take care of the rest. Law got the word to Oertle, who set out to locate Johnson.

It had been more than a year since Oertle had been in contact with him, and it took some digging before he learned the bitter truth and got it back to Law; Johnson had died recently under uncertain circumstances. In truth, Robert Johnson had been poisoned for gtting too close to somebody else’s woman one time too many.

Robert Johnson was buried in a wooden coffin that was furnished by the county. His mother, brother-in-law, and later his half-sister Carrie all visited his grave in, as recent research indicates, the graveyard of the Little Zion Church just north of Greenwood, Mississippi. That particular stretch of county road, which eventually delivers the travaler to the hamlet of Money, Mississippi, is commonly referred to as, “the Money road”.

Hammond, by the way, got Big Bill Broonzy.

When you got a good friend by Robert Johnson (1936)

When you got a good friend, that will stay right by your side.

When you got a good friend, that will stay right by your side

Give her all of your spare time, love and treat her right

I mistreated my baby, and I can't see no reason why

I mistreated my baby, but I can't see no reason why

Everytime I think about it, I just wring my hands and cry

Wonder could I bear apologize, or would she sympathize with me

Mmmmmm mmmm mmmm, would she sympathize with me

She's a brown skin woman, just as sweet as a girl friend can be

Mmmm mmmm, babe, I may be right ay wrong

Baby it's yo'y opinion, oh, I may be right ay wrong

Watch your close friend, baby, then your ene'ies can't do no harm

When you got a good friend, that will stay right by your side

When you got a good friend, that will stay right by your side

Give her all of your spare time, love and treat her right

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario